The extraordinary growth of Pentecostalism in Africa cannot be fully understood without examining its profound cultural resonance with African worldviews and social realities. Three key factors have contributed significantly to the movement’s appeal across diverse African contexts.

The Holistic View of Life

Traditional African societies have historically maintained a holistic understanding of reality that integrates spiritual and physical dimensions of existence. Within these cultural frameworks, spirituality and health are inseparably connected. African communities were largely health-oriented, with traditional religious practices centered on rituals for healing and protection. The traditional healer or “spiritist” served as an intermediary who addressed physical ailments by confronting their presumed spiritual causes.

This worldview contrasts sharply with the dualistic perspective often characteristic of Western Christianity, which tends to separate physical and spiritual concerns. In African thought, no rigid dichotomy exists between the material and spiritual realms—they form a continuous, integrated reality. The holistic approach of Pentecostalism, which addresses both spiritual salvation and physical healing, found immediate and overwhelming acceptance in African contexts precisely because it aligned with this traditional understanding.[^1]

As defined, the term “holistic” here refers to “including or involving all of something, especially all of somebody’s physical, mental, and social conditions, not just physical symptoms, in the treatment of illness.” This comprehensive approach resonates deeply with traditional African conceptions of wellbeing.

Across Africa, a major attraction of Pentecostalism has been its emphasis on divine healing. In African cultural understandings, the religious specialist or “person of God” possesses supernatural power to heal the sick and counteract malevolent spiritual forces. The Pentecostal movement effectively reclaimed this holistic function, refusing to separate physical health from spiritual vitality, and thereby addressing a dimension of human experience that more rationalistic forms of Christianity often neglected.[^2]

Immediate Personal Experience

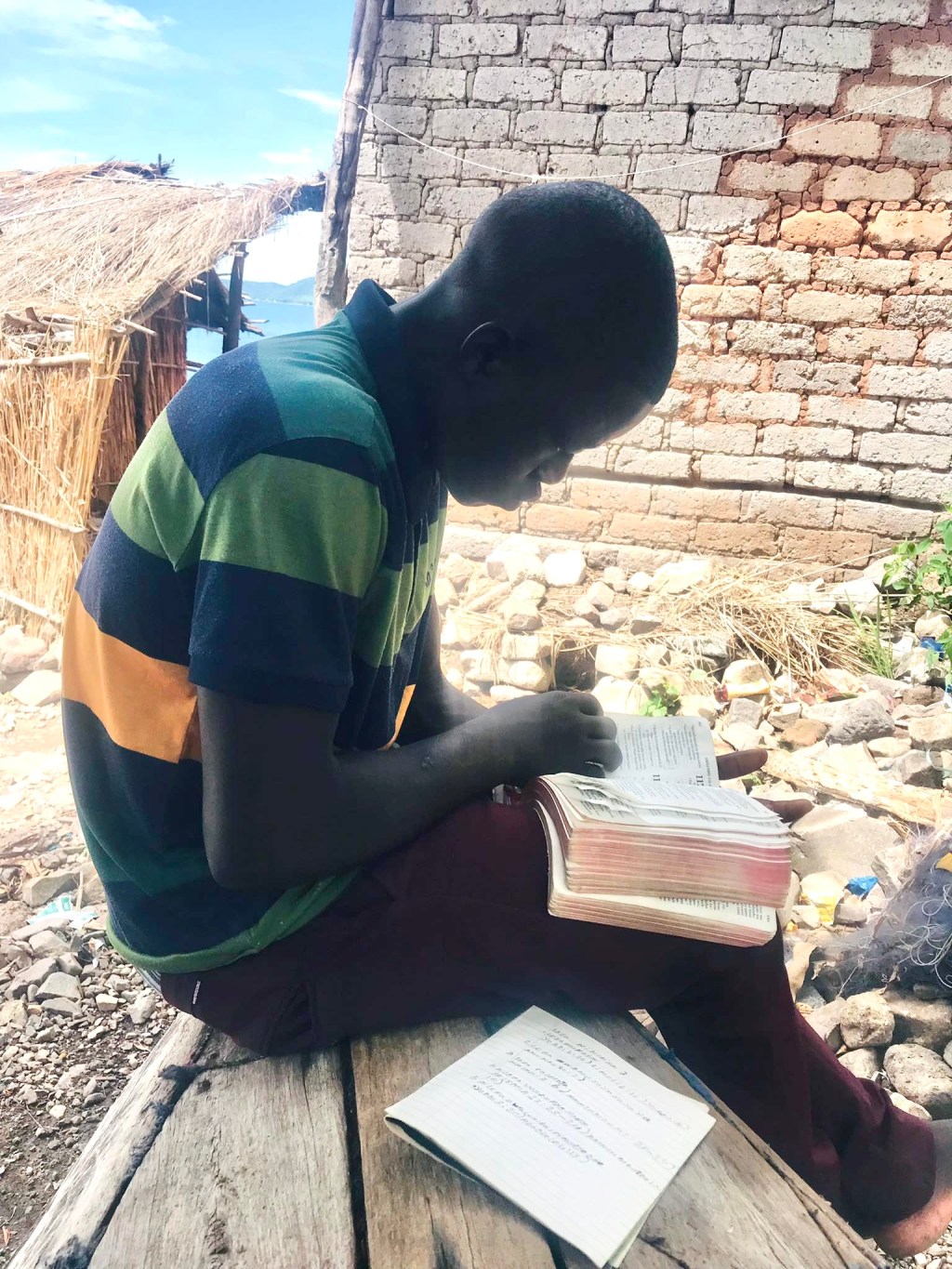

A second cultural factor contributing to Pentecostalism’s appeal in Africa involves its emphasis on immediate spiritual experience. Across many African societies, daily life is oriented toward the personal and immediate rather than distant abstractions or future possibilities. Experience is fundamentally present-tense, with less emphasis on long-term planning characteristic of some other cultural orientations.

The Pentecostal emphasis on direct, personal experience of God’s power through the Holy Spirit aligns naturally with this cultural predisposition. Pentecostal Christianity offered immediate, tangible solutions to pressing concerns—illness, spiritual oppression, poverty, and other challenges. Its acceptance was predicated more on shared experience and practice than on doctrinal formulations or theological abstractions.

Furthermore, the Pentecostal approach to spirituality tends to be more intuitive and emotionally expressive, qualities that resonate with many African cultural expressions. The movement’s recognition of charismatic leadership and indigenous church patterns wherever they emerged further facilitated its cultural adaptation across diverse African contexts.[^3]

Freedom in the Spirit

A third significant factor in Pentecostalism’s African success has been its inherent flexibility. What Harvey Cox describes as “freedom in the Spirit” enabled the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement to adapt fluidly to various cultural and social environments. As Cox observes, “The great strength of the ‘Pentecostal impulse’ lies in its power to combine, its aptitude for the language, the music, the cultural artifacts, the religious imagery…of the setting in which it lives.”[^4]

This adaptability stands in marked contrast to the approach of many traditional missionary churches, which often arrived with predetermined liturgies, theological systems, highly educated clergy, and centralized leadership structures. These external forms contributed significantly to the perception of such institutions as “foreign churches” disconnected from local cultural realities.

The Pentecostal movement’s emphasis on direct spiritual guidance permitted greater indigenous expression and contextual relevance, allowing African Christians to develop culturally authentic expressions of faith that addressed their specific circumstances and concerns while maintaining connection to the global Christian community.

Conclusion

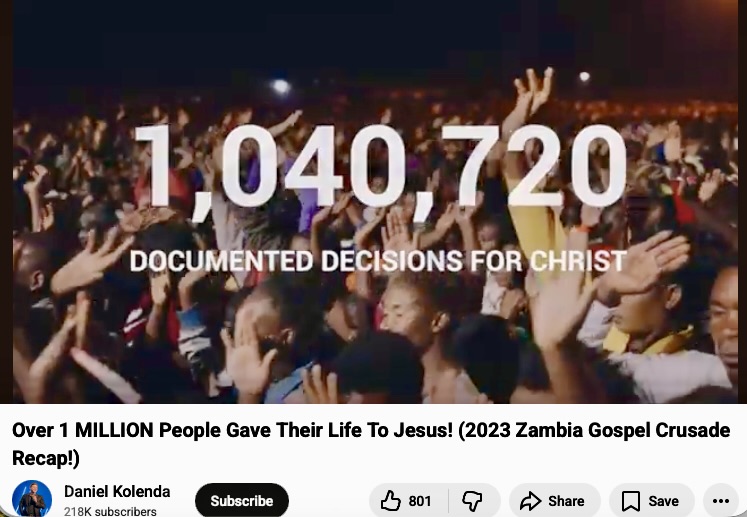

The African traditional worldviews provide fertile soil for the theological seeds of the Pentecostal Charismatic movement. The emphasis on a holistic understanding of healing, immediate spiritual experience, and flexible religious expressions explains the extraordinary growth of the movement in Africa. The outcome of this syncretistic understanding of Christianity raises questions about its biblical authenticity. As we will explore in subsequent discussions, this cultural adaptability—however strategically successful—may have come at the cost of theological integrity, genuine conversions, and biblical churches in Africa.

[^1]: This alignment between Pentecostal holistic approaches and traditional African worldviews has been identified by numerous scholars as a key factor in the movement’s extraordinary African growth.

[^2]: The emphasis on healing addresses a dimension that rationalistic Western theological approaches often neglected, creating greater resonance with traditional African religious concerns.

[^3]: The present-tense experiential orientation of much African cultural expression found natural alignment with Pentecostal emphases on immediate spiritual experience.

[^4]: Harvey Cox, Fire From Heaven: The Rise of Pentecostal Spirituality and the Reshaping of Religion in the Twenty-First Century (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1995), 102.

Leave a reply to Bickson Cancel reply