Introduction

The Pentecostal Charismatic movement represents one of the most significant religious phenomena in modern African Christianity.

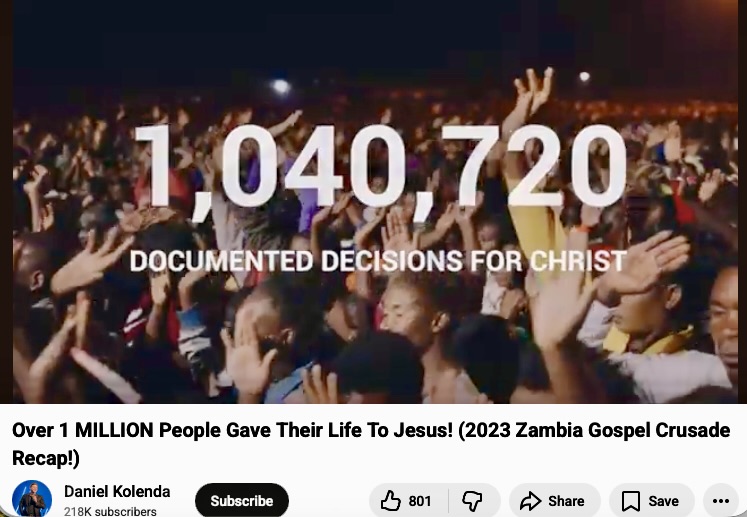

Within a single century, this movement has grown from obscure beginnings to become perhaps the dominant expression of Christianity across the African continent, outpacing traditional mission-established denominations, Catholicism, and even challenging the growth of Islam in many regions. This remarkable expansion demands careful analysis, particularly for those seeking to understand the contemporary religious landscape of Africa.1

This blog series will examine the historical developments, theological foundations and hermeneutical approach of the African Pentacostal Charismatic movment. We will see how this movement resonates closely with traditional African worldview based on African traditional religions. The promise of supernatural power and financial well-being contributing significantly to its widespread appeal in Africa. We will provide a biblial critique of key charismatic teaching and offer a framework for theological engagment with those within the Charismatic movement in Africa.

The History of the Pentecostal/Charismatic Movement in Africa

Part 1 – Beginnings in North America

The global Pentecostal movement traces its origins to events in the United States at the dawn of the twentieth century. In 1900, Charles Fox Parham, a former Methodist pastor, founded Bethel Bible College in Topeka, Kansas, with a distinctive approach that utilized the Bible as the sole textbook for students. During the Christmas break of that year, Parham assigned his students to investigate the biblical evidence for the baptism of the Holy Spirit. The conclusion that they reached was that speaking in tongues constituted the evidence of Spirit baptism.2

This theological conclusion soon found experiential confirmation. On January 1, 1901, after a night of prayer and fasting, a student named Agnes Ozman requested that Parham lay hands on her to receive the gift of the Spirit, accompanied by the evidence of speaking in tongues. According to accounts, she became the first to experience this phenomenon, followed by several others in the days that followed. This event, though small in scale, marked the beginning of modern Pentecostalism.3

The movement gained crucial momentum through William Joseph Seymour, an African American preacher and son of freed slaves. In 1905, Seymour traveled to Houston, Texas, where Parham had established another Bible college. Despite being forced to listen to Parham’s lectures from outside the classroom due to racial segregation policies, Seymour became convinced of Parham’s teachings on tongues as evidence of Spirit baptism.4

In 1906, Seymour was invited to preach at a black holiness church in Los Angeles, California. After delivering a sermon on tongues, he was asked not to return. However, members of this church began meeting with Seymour for prayer in a private home. During one such gathering, Seymour laid hands on the African American Baptist pastor who was hosting him. The pastor reportedly fell unconscious and subsequently began speaking in tongues. Seven others, including Seymour himself, had similar experiences. As these prayer meetings grew, even white participants began attending—a remarkable development in the segregated America of that era.

The expanding group soon relocated to an abandoned building on Azusa Street, which the African Methodist Episcopal Church had formerly owned. There, the Apostolic Faith Mission was established. For about three years, daily meetings beginning around 10 a.m. and often lasting late into the evening. These services were characterized by their spontaneous nature. They lacked formal liturgical structure or designated speakers.

The Azusa Street Revival became the epicenter of early Pentecostalism, with its influence spreading nationally and internationally. Today, twenty-six different Pentecostal denominations trace their origins to this revival, including the Assemblies of God, which would become the largest Pentecostal denomination globally.5

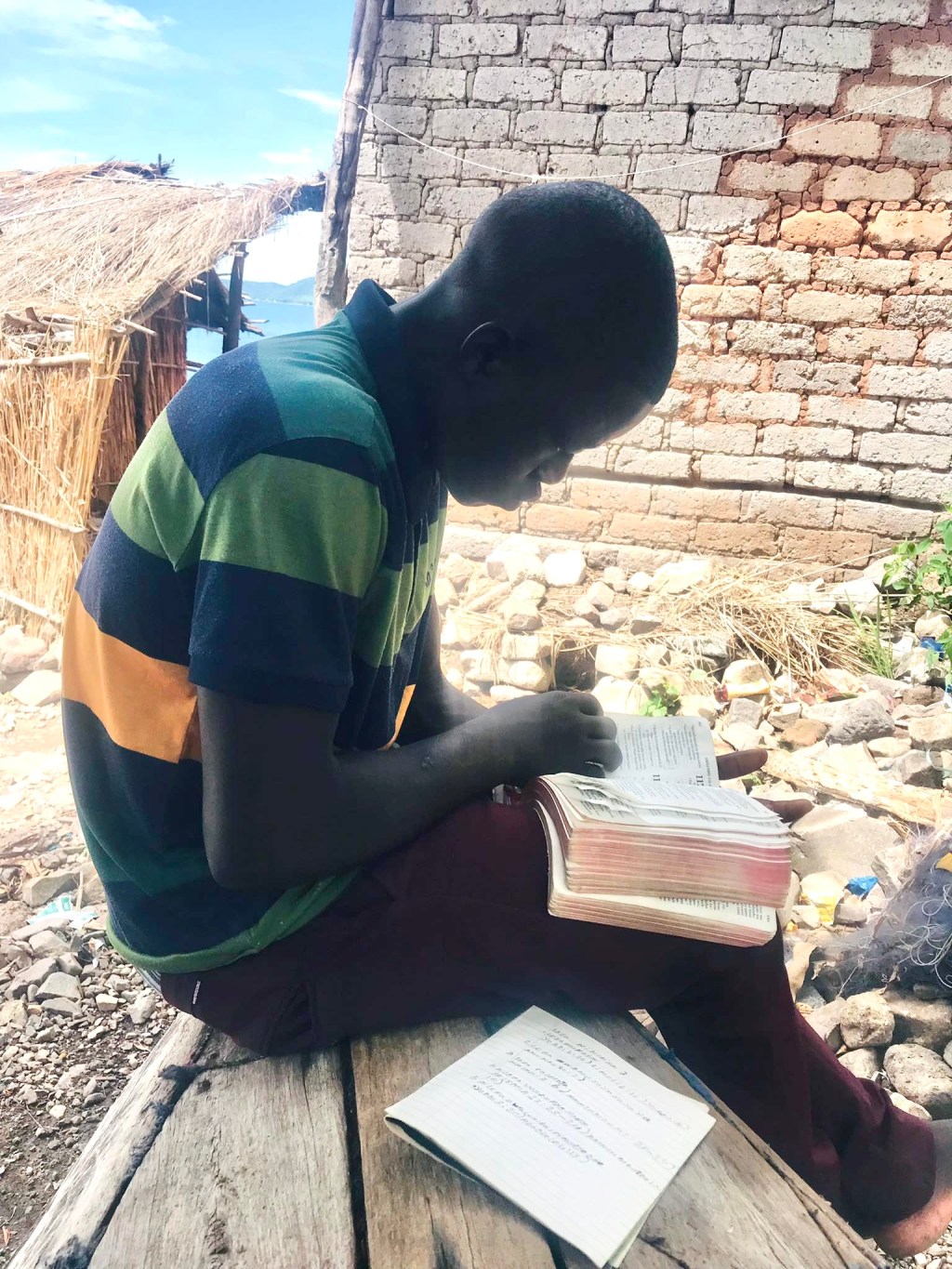

The journey from a small Bible college in Kansas to the gatherings on Azusa Street reveals how quickly and powerfully spiritual movements can emerge and spread. What began as a theological inquiry by a handful of students would ultimately reshape Christianity across continents, with Africa becoming one of its most receptive.6

As we continue this series, we’ll explore how these early Pentecostal seeds took root in African soil, adapting to local cultures while maintaining their core emphasis on the immediate experience of God’s power. Understanding these origins provides essential context for appreciating both the universal appeal and the distinctly African expressions of Pentecostalism that would emerge across the continent of Africa in the decades to follow.

- (TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH: PENTECOSTALISM AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF WORLD CHRISTIANITY. By Allan Heaton Anderson. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.) ↩︎

- I am indebted to numerous online articles and personal correspondence with Dr. Allen Anderson, who has studied and written extensively on this subject, with much of his research conducted in South Africa. ↩︎

- The events at Bethel Bible College in 1901 are widely recognized as a key starting point for the modern Pentecostal movement. However, some scholars note precedents in the Holiness movement and earlier revival phenomena. ↩︎

- The racial dynamics at play in early Pentecostalism reveal both the movement’s progressive aspects (relative to its historical context) and the persistent racial barriers that Seymour and other African American leaders encountered. ↩︎

- The Assemblies of God, founded in 1914, has grown to become one of the largest Pentecostal denominations globally, with a significant presence across Africa. ↩︎

- 115,000,000 pentacostal charismatics in Africa. The World’s Christians: Who they are, Where they are, and How they got there. By Douglas Jacobsen. https://books.google.co.zm/books?id=6bivgXYZbuoC&pg=PT2&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=1#v=onepage&q&f=false ↩︎

Leave a comment