I suppose some might call me old-fashioned, but I can’t help wondering where the respect for elders has gone. The other day, I was sitting with a friend in church when a boy, maybe 10 years old, walked by, called out my friend’s first name, and gave him a casual high-five. I don’t entirely blame the little boy—children act as they’re taught. Where are the parents instilling respect in him? Respect for authority, and for adults in general, doesn’t just appear—it takes time and intentional teaching. Watching that moment unfold got me thinking about how I was raised and what I’ve learned about other cultures, like those in Zambia, where respect for elders is a cornerstone of life.

Lessons from Traditional Zambian Culture

In Zambia, a country with over 70 ethnic groups—like the Bemba, Tonga, Lozi, and Nyanja—respect for adults is deeply rooted in tradition. Children don’t just call adults by their first names; they use honorific titles that reflect their place in the community. Among the Bemba, for instance, an adult might be addressed as Tata (father) or Mayo (mother), even if they’re not related by blood. The Tonga use Baama (mother) or Baata (father), while older folks might be called Shikulu (grandparent) or Mukulu (elder) across various groups. These titles aren’t just words—they signal that every adult is a guide, a teacher, someone worthy of reverence.

It’s not only about what children say but how they say it. In Zambian culture, kids are taught to speak politely, with a soft tone, avoiding direct confrontation. A child might say, “Excuse me, Auntie, may I please…” rather than barking out a demand. And it goes beyond words—non-verbal respect matters too. In rural areas especially, children might bow slightly, lower their eyes, or even kneel when greeting an elder. They don’t interrupt when adults are talking; they wait their turn. Offering to carry something for an adult is another quiet way to show deference. Calling an adult by their first name without a title? That’s often seen as disrespectful because it implies equality, erasing the hierarchy that honors age and experience.

This respect is reinforced through proverbs and stories. Among the Bemba, there’s a saying: “Umwana ushiba mayo afweni kuli tata”—a child who doesn’t know its mother seeks help from its father. It’s a reminder that wisdom flows from elders, and children are expected to listen and learn. Across Zambia’s cultures, every adult in the village is seen as a guardian to every child, not just their own parents. It’s a communal approach that drills in the idea: respect isn’t optional; it’s foundational.

My Own Upbringing and Observations

Growing up, I was taught to address adults as “Mr.” or “Mrs.”—a simple rule that set them apart as authority figures. We were not allowed to respond to an adult with slang like, “huh?”, “yup” “yah,” we were expected to say, “Yes Sir,” or “No maam.” Whatever form it takes, respect for elders must be taught consistently and upheld diligently. But today, I see children acting as if they’re equals with adults. They call them by first names, interrupt conversations, and jump in without hesitation. That boy in church didn’t think twice about calling my friend by his first name like they were age-mate buddies. There’s some truth to the old sayings, “Children should be seen and not heard,” and, “You speak when you are spoken to.” Proverbs talks about a child gaining wisdom by watching and listening—to fathers, to elders, to those with experience. One way a child grows wise is by sitting quietly at the feet of those who’ve lived longer.

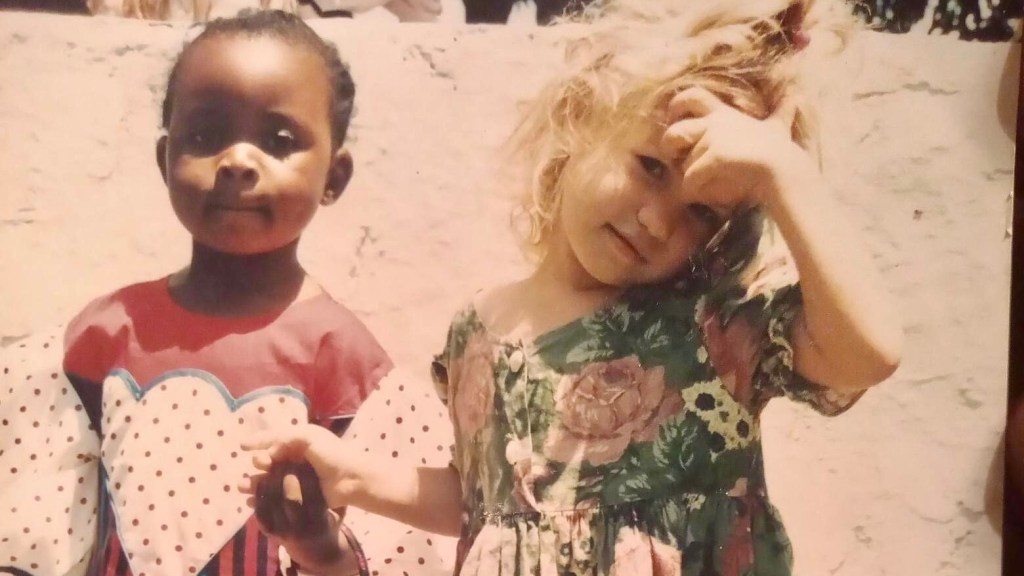

We can’t disciple our children if they’re always talking or if they feel they’re on equal footing with the adults around them. While they are of equal value as those created in the image of God, they are not of equal authority. There’s a time and place for a child to speak, ask questions, and engage with adults, and they need to be taught when those moments are. I’ve noticed in some missionary communities, and even in places like Zambia, that terms like “Aunt” or “Uncle” get used—not out of familiarity, but as a mark of respect. It’s a way to avoid casualness and keep that sense of reverence alive. When a child calls an adult by their first name alone, it chips away at the idea that age and experience command something special.

Where Tradition Meets Today

In Zambia, these traditions still hold strong, especially in rural areas where kneeling and formal greetings are common. But in cities, modernization and influences like Westernization have softened some practices—kids might say “Mr.” or “Mrs.” in school instead of traditional titles. Still, the core value remains: Elders are custodians of wisdom, and children are raised to honor that. Here, though, I worry we’re losing it altogether. That high-five in church wasn’t malice—it was ignorance of a boundary that should’ve been set. Parents, communities, churches—we’ve got to teach it, or it fades.

There’s a balance to strike. Kids should feel loved and heard, but they also need to know their place. When I think about Zambia’s ways—those titles, those gestures, that quiet listening—it’s not about silencing children; it’s about preparing them. If they don’t learn to respect and learn from elders now, how will they grow into adults worth respecting later? I’m left asking: if we let this slip, what else do we lose along the way?

Leave a comment